How to (Not) Crash Out

White people don’t crash out, they go bezerk. Lilly writes on ruts, and getting out of them.

When I was 19, I totaled my car. With my friend in the passenger seat, I was driving from Long Island to Brooklyn, to see a band I wrote about in a tiny music magazine that was based out of the editor’s living room. I wasn’t a reckless driver, just a relatively inexperienced one — so when the sun hit my direct eye line as I was exiting the highway, I clipped the median. I know we spun out because of where we ended up, but there was no moment when I processed any motion. One second I was driving, and the next I wasn’t. I was just sitting in the driver’s seat, shouting. It felt like teleportation. By dumb luck, we didn’t hit anyone else or get injured. We called 911, but the cops didn’t bother to show up — just the tow truck driver, who insisted on taking a video of the damage to post on his Instagram account, where he posted all of the totaled cars he towed, and our other friend’s mom. She drove me back to her house, where I was staying that summer, and honored my request when I asked to be left alone for the rest of the night.

Two days later, I called the insurance company because people kept asking me if I had. I filed a claim over the phone quietly and through nerve-induced tears, like a shy child being forced to order the pizza for the first time. The agent was kind to me and very patient. In his nasally, harmless sounding voice, he explained that he just needed a few more documents from me to confirm I was covered by the policy.

“I’ll send them today,” I lied before hanging up.

He believed me, I’m sure, because this was the first time I was talking to him. That would soon change.

The insurance agent didn’t know that to get the documents he was asking for, I’d need to go back to my childhood home — which was a 10-minute drive that I’d been refusing to make for the past year. Nor did he know that, after my dad died in the backyard of that home a few months before my 18th birthday, I’d started experiencing a kind of paralysis that prevented me from doing things I really knew I ought to be doing. Melinda and I joked about how sometimes she’d wake up in our dorm room to find me already awake, staring at the ceiling. I did it almost daily, desperate to just be motionless for thirty minutes, an hour, to live in the last moments I saw him.

I dodged the insurance guy for weeks, until I got back to school a few states away. In my dorm room in Boston, I felt safe enough to pick up one of his calls. I apologized to him profusely and explained how busy life was. I told him about my dad, about why everything was so messy, in a way I hadn't told some close friends — maybe because he didn’t feel like a real person to me. Again, he was kind to me. He said my name a lot in conversation, which reminded me that I was a real person.

“Usually, Lilly, we have a hard time getting track of people who owe us money,” he said with a breathy laugh. “Not the other way around.”

I knew when I told him I’d get the documents soon, over Thanksgiving break, he would believe me less — and less when I said the same thing about winter break. And even less when we started communicating exclusively over voicemail, when I learned the times to call when he wouldn’t be in his office.

I didn’t know how to explain to him that I wasn’t interested in doing anything I didn’t already know how to do, that I hadn’t been in a long time. I knew how to do schoolwork, I knew how to talk to a select group of people, and I knew how to lie about what was going on in my life. None of this was going to help me successfully file an insurance claim.

Eventually, about six months later, a friend of my mother’s caught wind of what I was doing and stepped in. I don’t know how or when, but she found what I needed and submitted the rest of the paperwork, completely removing me from the process. I knew it was over when I got a voicemail from the insurance agent telling me that the money had been sent: a few thousand bucks, less than I had originally given my dad to contribute to the down payment. I was grateful to both of them, but never thanked anyone or really mentioned it ever again. For months, whenever I remembered how I treated them — this kind friend, this insurance agent whose job I made hell — I’d get the chills and physically shake a little.

What I wanted most was to never be so stuck, and so ashamed of myself, again. If I was in a hole, I resolved, I was going to climb. When graduation neared the next year, I applied to jobs and internships across the country, desperate for a way to start my life anew. I didn’t hear back from any of them, except for one at a tiny three-person newsroom in Skagway — a tourist-driven city in Southeast Alaska that I had visited with my grandmother on a cruise a decade earlier. I accepted the summer role as soon as I got the offer. Almost 4,000 miles away, I learned how to eat in public alone, how to hike using my own internal compass, and how to envision a future that didn’t end with me feeling as miserable as I had been every day I spent without my dad. When I moved back to Boston four months later, partially for another small magazine job and partially to pursue a relationship with my now-husband (at that point, just some guy I’d met right before I left), I was so much less embarrassed to be who I was. The trip had given me a blueprint for being on my own, a confirmation that I could will myself to do anything, an excitement for life again, a cool story to tell people (or myself) when I felt small.

It’s taken some work, but I’ve spent the years since I left Skagway leaning into my favorite trait: That I am a dynamic person, who embraces new things. I love that, as an adult, I learned how to ride a bike and to play tennis. I love that I finally learned how to run without feeling like there’s a sack of rocks in my lungs, to knit a sweater, to make croissants and profiteroles from scratch. That I’ve changed careers and made new close friends, which seemed impossible when I was moving hours away from the ones I loved so much already. I love that I’ve invested a lot of time — and pushed through a lot of embarrassing failures — into creating a life that I look forward to every day.

Most of all, I love that I know how to dig deep when I need to, now that I’ve done it once before. On a balmy day in June of last year, I was assistant teaching a croissant class at an adult education center. I had helped with this class a handful of times before, but this had been a particularly frustrating session. It was too warm, and the butter kept melting out of the students’ puff pastries. Clean up took longer than I expected. After eight hours on the clock, I was exhausted. When my husband came to pick me up, I dragged my feet to the car. “I can’t do these all day sessions anymore,” I told him. He agreed and helped carry my stuff up the stairs into our apartment.

Not long after I vowed not to get up from the couch again the rest of the night, I stood up to go to the bathroom and I tripped. On none other than my own Birkenstock sandal, which I had lazily left in the hallway. We were in the process of moving (my suggestion, of course) and there were boxes everywhere; I crashed into them as I fell. Like the car accident, I didn’t understand anything on the way down. There was just the moment before I fell, and the moment where I was shouting, knowing that my foot had bent at an angle it had never bent at before. We were back in the car, on the way to the emergency room, about 10 minutes later.

The young doctor who was managing the floor that night told me I was lucky as he showed me the X-ray of my broken bone. I probably wouldn’t need surgery, even though they usually operate when the break is as high as mine was. “I think summer can still be fun,” he told me with a smile as a nurse came in with a boot and a pair of crutches. I’d need to use the crutches for three weeks, wear the boot for the following three weeks, and then switch to a sturdy running shoe for three weeks after that. If I deviated from the plan, I risked displacing the bone and needing surgery after all.

I cried that night, and told my husband I was scared. I had never broken a bone before; I had never been unable to get my own glass of water. For three weeks, he helped me get in and out of the shower, where he had placed a shower chair for me. He got me glasses of water. When it was time to go to bed — up a flight of stairs that was too winding and narrow for crutches — he cheered me on as I sat on my butt and pushed myself up each step with my arms. When I woke up having to go to the bathroom at night, he got up, too — to help me down and back up the stairs again. I felt myself start sinking again, thinking only of how little I could do. I spent a few entire weekend days staring at the TV in silence, but I tried to resist the temptation. I bubble-wrapped and packed boxes. By the time we actually moved, I was still in a boot but I was able to walk again — so I got to work on decorating our new apartment. I followed all of the doctor’s orders, walking thousands of steps per day in my boot and then my running shoe, even when my foot ached, because he told me it would help me heal. I felt pride in my easy recovery.

A month and a half after I was cleared to return to my regular activities, I felt another pain. This time, in my abdomen. I was used to stomach pain after years of digestive issues, but this was different. It felt like a balloon was in my stomach, expanding, trying to find space to grow in my chest, threatening to explode inside me. I ignored it for a few hours, until I got home from work and I couldn’t think about anything besides the pain. This emergency room visit went differently. I'd need surgery. A PA on duty told me that I was going to have my appendix removed as soon as they could prep an operating room. When I asked if there was anything I could have done to prevent it, he shrugged. “It’s just bad luck,” he said, before offering me a hug.

When we got home, my husband once again helped me up the stairs — four flights to our new apartment. I was told not to lift anything, not even a carton of milk or a grocery bag, for at least three weeks. So, for the second time in our first year of marriage, he physically lifted me in and out of bed as my abdomen muscles seared with pain, in and out of the shower, on and off the toilet. He told me it might make me feel better to work on something, like the book I was writing, and I said I’d try without moving toward my laptop. Secretly, guiltily, I hoped he’d stop. I thought of my mom’s friend, digging through old papers in the mess of my childhood home. The agent calling me, just so that I could lie to him again.

The helplessness I was feeling brought me back to a really difficult part of my life, but something was different this time: I couldn’t sink as deeply, even if I wanted to. I’d made too many changes. What I didn’t know then was that, one day, I’d learn how to ask for help without being so embarrassed. I’d find new hobbies, like knitting or baking, that made me feel productive but free of the pressure I sometimes feel when writing. Little ways to move, even when I was told I had to stay still.

Early in our relationship, I used to tell my husband that I was constantly afraid that the other shoe was about to drop. Not long after we got married, I started telling him that I was so happy I felt like it never would. Really, I learned that believing in either of those options is a useless exercise. Predicting that a bad thing will happen — or assuming it won’t — doesn’t make it any easier to address it at the moment of impact. Would you believe me if I told you I had looked up the symptoms of appendicitis hundreds of times in my life, but I tried to walk out of the emergency room before they had a chance to diagnose me because I didn’t want it to be true?

What is productive, at least for me, is accepting that I’m a person constantly in flux, turning over good and bad stones (and tossing one in my pocket every now and then). After all, I find something new under each one. I learned that on an empty trail in Skagway, on a bike seat with no one behind me holding the handlebars, on a vinyl examination table in a paper gown. I learn it every time I sit down to write this newsletter. — LM

Hunter-gatherer corner

What we’ve read and DMed each other about lately — our internet bounty is below!

“Among the Post-Feminists” by Grazie Sophia Christie - The Point Mag — I first learned about feminism as a tween scrolling Tumblr, in the hey-dey of sex positivity and millenial #girlboss culture, when using the word “woman” to describe anyone below the age of 40 still felt weird and too grown up to me. Now that I actually am a woman, I’m learning how to make feminist choices in a world where choice feminism and “soft girl” culture and trad values and “divine femininity” and “26-year old teenage girls” are dominating the conversation on womanhood. None of it has ever felt like it fits, then or now. In this piece, Christie’s take on this feeling is unlike others I’ve read, and I recommend the read. — LM

“The ‘White Lotus’ smile discourse is actually pretty condescending” by Valerie Monroe - Allure — While I feel like this headline is overly pointed, I did enjoy this analysis of the way we discuss teeth in the time of Big Veneers. As someone with a front gap who purposefully had my dentist preserve it during my Invisalign days, I’ve genuinely never understood the idea that unique teeth were unattractive. But that’s the thing about beauty and status markers — they’re all relative. —MF

Why Not?

Why Not? is our biweekly list of recommendations. Think recipes, gift guides, podcasts, clothes, and anything we consider to be generally chic. Have a suggestion? Let us know!

Sofie Pavitt Face Mandelic Acid Exfoliating & Clearing Serum - Sephora — This was my favorite pickup at the sale last week. It’s super gentle, so anyone who tends to overexfoliate will be safe with this one. I totally understand why people are loving this serum now —I’m just getting off my cycle, and this has given me a total texture revamp after just a few uses. ICYMI: our top 75 Sephora product masterlist is here. From our top 20 picks, you all seem to be really loving the Danessa Myricks Blurring Balm Powder, the Violette FR Bisou Balm Matte Lips, and the Eadem Le Chouchou Lip Balms (which are now back in stock in the clear shade, FINALLY — run!) —MF

Arahi 7 - HOKA — My sturdy running shoe of choice (in the Blanc De Blanc / Rose Gold color)! — LM

Yap Year by Daysia Tolentino — Our friend Daysia has launched a must-read newsletter over on Beehiiv. Her writing is voicey, fun, and she shares the best pop culture news along with a playlist every week. She has a real talent for archiving and contextualizing the highs and lows of Gen-Z-millennial cusper content, so if that’s of interest to you, subscribe! I’m always thrilled when I see Yap Year has hit my inbox. —MF

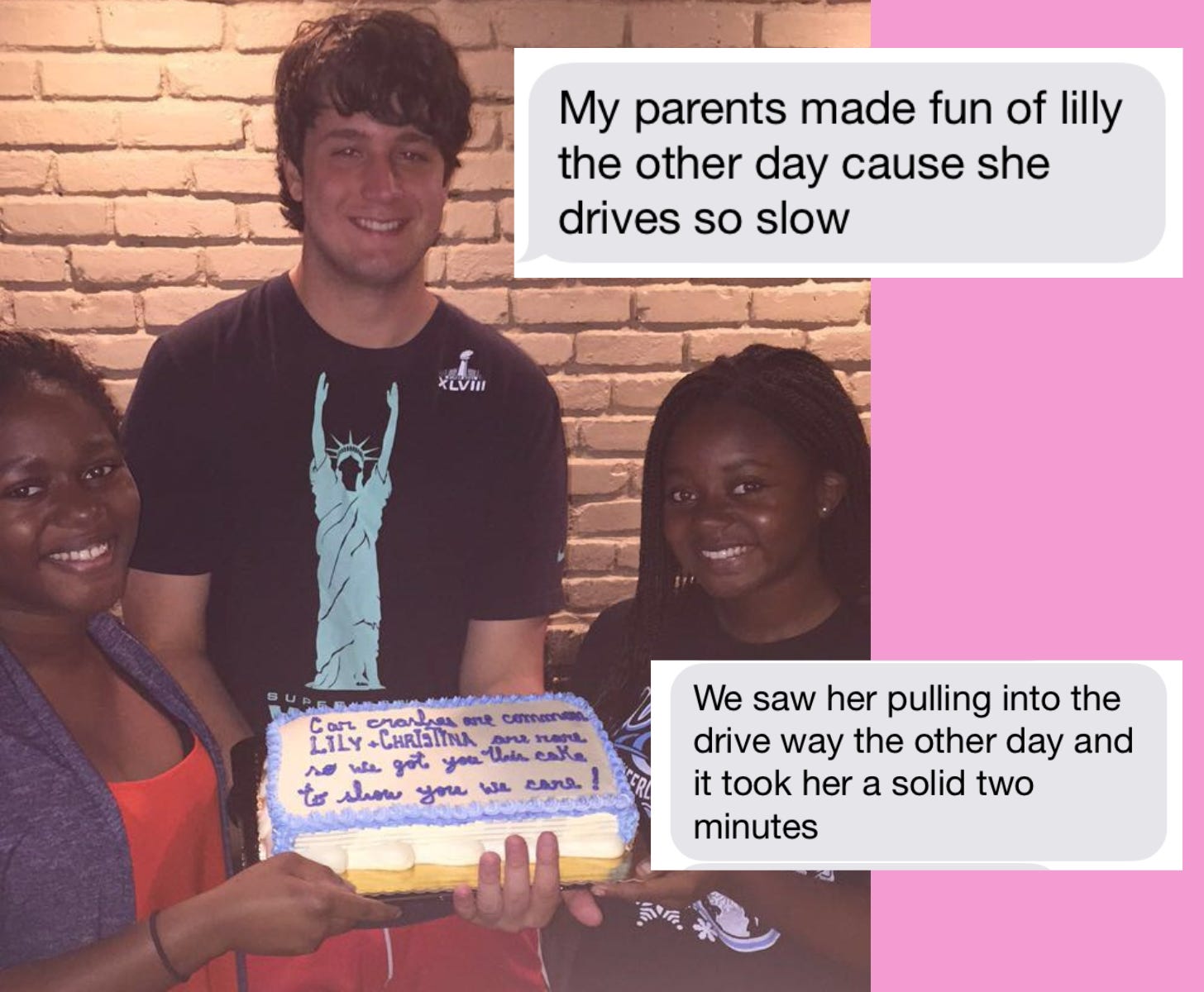

If you liked this issue, do NOT crash out! Tell us your thoughts in the comments or on Instagram (@lilly_milman | @melindafakuade), and share it with the person who’ll show up at your door with a car accident cake.